The Carter-Leslie Doomsday Argument is a probabilistic argument that claims the expected lifetime of humanity is proportional to the number of humans that have existed so far. More specifically, the chance of being part of the first 1% of humans is only 1% – so there might be a 99% chance of humans going extinct before reaching 100 times the number of humans that have existed so far.

This article contains a simulation that provides a counter-argument to the Doomsday Argument by arguing that one's position in the list of existing humans is independent of the total number of people. I will soon write a second article in which I go a bit deeper into the philosophical theory that constructs this bizarre problem.

Bayesian lottery

The Doomsday Argument was first introduced to me by a similar question: suppose you're participating in a lottery. You don't know how many others participate, but you are told that there's a 50% chance that 10 people participate, and there's a 50% chance that 1 trillion people participate. If you draw lottery number 5, what does that tell you about how many people participate?

Both one's intuition and Bayesian statistics tell you that the likelihood heavily favours the option where only 10 people participate, as drawing a ticket under 11 is a marginal chance in a trillion ticket lottery. With the Doomsday Argument, however, this logic can draw an emotional reaction from people: people don't want this logic to make sense, as the Doomsday Argument sounds rather chilling: with the recent population boom we've made, it suggests that the apocalypse is very likely imminent in a few generations.

At first, I wasn't too interested in the problem: I dismissed it as 'Bayesian trickery' – my own term for abusing Bayes' theorem to support wild claims. For example, people have used it to argue that we live in a simulation, that we must build a murderous AI superintelligence to avoid extinction and that God exists because miracles occur. Such arguments have brought me a certain level of skepticism for outlandish claims relying on Bayesian statistics. My counter-argument might be flawed or be utterly nonsensical, but my gut feeling remains that the Doomsday Argument is a well-crafted example of Bayesian trickery that has remained untamed for several decades now.

Simulations

Personally, I am a fan of using numeric simulations to make converging approximations of probabilities, as they help gain insight into how chances work.

For example, to simulate the lottery problem, the following script can offer some insight:

import random

N = 1_000_000

a, b = 0

# Sample N times

for _ in range(N):

if random.random() < 0.5:

# The lottery has 10 participants

a += 1 if random.randint(1, 10) == 5 else 0

else:

# The lottery has 1 trillion participants

b += 1 if random.randint(1, int(1e12)) == 5 else 0

# When drawing 5, this number represents the fraction of times the lottery had 10 participants.

# This number should be near 1.

print(a / (a + b))

We can even calculate that this fraction should converge to $\frac{\frac{1}{10}}{\frac{1}{10} + \frac{1}{10^{12}}} \approx 1 – 10^{-11}$.

Nevertheless, with a similar simulation, I will demonstrate how this analogy does not go for the Doomsday Argument.

Bug world

Enter Bug World, a hypothetical planet in our galaxy that hosts a wide variety of bugs that have a peculiar species lifetime. We'll test whether being “early” in humanity means doom is near, and we'll do that by having only some bugs thrive on Bug World. This lets us ask: do early bugs have reason to believe their species will end soon? Let's simulate!

On Bug World, every species is destined to go extinct after 10 bugs or after 1000 bugs. (We could've said 1 trillion, but that's too intense to simulate on contemporary hardware.) All bugs reproduce asexually and immediately die when they give birth, so there's always exactly one bug of every species alive. The 10th bug has a 50 percent chance of dying without reproducing the 11th bug. If the 11th bug is born, however, the species is guaranteed to go extinct after 1000 bugs have been born.

Since we're going to run this simulation on many species, we'll call a species a mayfly type if it goes extinct after the 10th bug, and we'll call it a millipede if the species survives until its 1000th bug. We'll call a bug young if it is one of the first 10 bugs in its species, and we'll call a millipede old if it is the 11th or latter specimen.

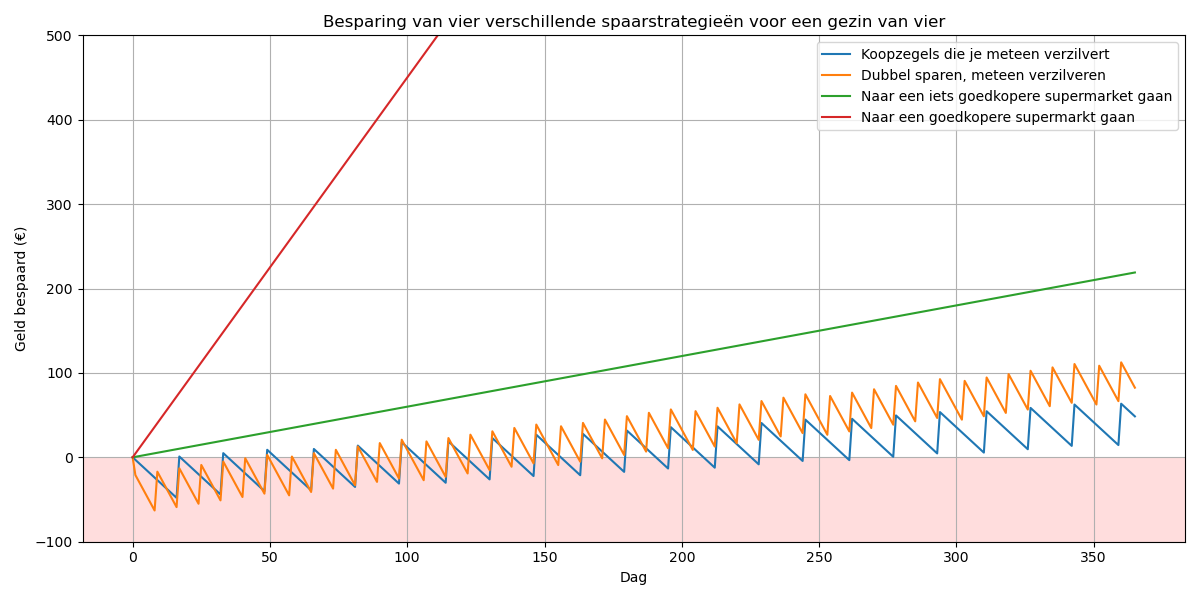

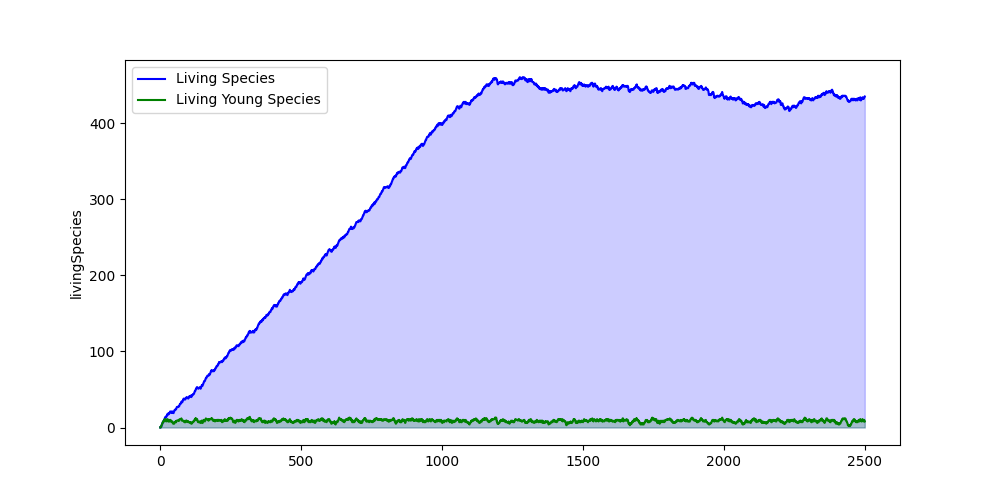

I have started a simulation. About every tick or so, a new bug species emerges in the world. At first, you notice a linear growth of new bugs, but the Bug World population stabilizes after the first millipedes start to go extinct. From there, the simulation mostly has a uniform distribution of all the bugs and their potential lifetimes.

The graph shows in blue how many bugs are alive at a time step. The green line below shows how many of those bugs are still young. For those bugs, it isn't determined yet whether they are mayflies or millipedes.

Let's sample some bugs! Bug World simulates species that may end early (like humanity might). Sampling bugs is like asking: “Am I, a humble bug, early in my species’ timeline?” If the answer is yes, we'll move forward in time to see when the species goes extinct.

When sampling bugs from Bug World, I got the following results:

We sampled 10000 bugs, of which 208 (~2%) were young bugs.

Old millipede: 9792

Old mayfly: 0

Young species ended up being a millipede: 107

Young species ended up being a mayfly: 101

======================================

Odds of a millipede species dying old: 100%

Odds of selecting a young bug when sampling a millipede: ~1%

Odds of selecting a millipede when sampling a young bug: ~51%

These results indicate an interesting revelation! We sampled 10K bugs, and we can translate the Doomsday Argument to this situation: instead of wondering our own human position, let's look at the position of all young bugs. When sampling a young bug, there's a 50% chance of selecting a millipede or mayfly – despite the odds of selecting a young millipede being minimal! This means that a young bug cannot conclude it is likely a mayfly because it is a young bug.

Why is this result different from the simplified lottery example? I believe that the flaw in the Doomsday Argument is that it believes that you, the observer, are guaranteed to exist in any case of the Doomsday Argument. However, for the bugs on Bug World, 99% of the millipedes wouldn't exist if their species had been a mayfly.

Fire Lottery

Let's reshape the lottery thought experiment in a way where it demonstrates how I think the Doomsday Argument should be imagined. For this new lottery, there's 1 trillion people willing to participate. However, there has been a fire at the lottery factory, so not every participant receives a lottery ticket! You do, however, and you receive ticket number 5.

To me, the lottery represents being born, and the ticket represents your number in human history. The unique part about the fire lottery, however, is that you do not know the total number of lottery tickets remaining.

You can try reasoning that it's unlikely that you ended up in the bottom 1% of tickets and therefore there's a 99% chance of at most 500 tickets having been printed, but that clearly doesn't work. It's easy to see that you're overlooking the massive chance that you wouldn't have received a lottery ticket anyway.

I believe that these lottery tickets represent human existence in our world. This explains why the odds don't shift for young bugs in Bug World, and it shows the independence between the total number of humans to exist and the number of humans that have existed so far.

Conclusion

The Doomsday Argument assumes that your position among humans is informative about how many humans there will be. But both Bug World and the Fire Lottery suggest otherwise: if your existence depends on many people existing in the first place, then being “early” says little about the total number. In other words, your ticket number only matters if you were guaranteed a ticket in the first place.

The concept of Bug World touches on underlying concepts that I will touch on in a future article. I'll post a link here when that topic is there, or you can click on any of the hashtags to view all posts on a given topic.

#bayesian #doomsdayargument #maths #philosophy

Older English post <<< >>> Newer English post

Older post <<< >>> Newer post